It’s no secret that Malaysia is gung-ho about cashlessness. Bank Negara Malaysia itself expressed as much, within the policies and guidelines outlined in their Interoperable Credit Transfer Framework (ICTF), and which PayNet, the system underlying much of payments and banking in Malaysia, has embarked on recently with the Real-Time Retail Payments system.

We certainly see the rationale. A cashless society is one that is more easily governed. Data of our spending habits are more easily accessible by regulators, and illegal activities, like terrorist funding can be more easily thwarted.

All of the benefits of cashlessness to a regular consumer have been well-documented as well, but hold your horses. Before we continue on our relentless march down this cashless road, here are some important things we should consider:

Let’s Face it: Cash is Just More Stable

Image credit: UpSticksNGo Crew on flickr

Think about a very typical problem: if your phone runs out of battery, would you suddenly find yourself completely penniless, despite actually being loaded? What if it was an emergency situation?

Meanwhile a bill that is worth RM50 will still be RM50, regardless of whether someone breaks into Bank Negara or if the internet happens to be offline that day.

The unreliability of intangible cash can have more far-reaching effects too.

In October last year, a cashless restaurant in Hollywood suffered a payment system crash, and forced the store to give away free lunches for everyone in line. Ironically, the lunch que that day would probably have gone quicker for that crowd had the restaurant accepted cash.

Now, imagine a similar crash, but on a bigger scale—what if WeChat Pay went down for a day in China? Or heaven forbid, if a whole nation’s payments system is down and out of the count. What would happen to Malaysia’s economy if our cashless systems were down for even 24 hours?

You’d Be a Glitch Away from Losing Everything

Image Credit: Pixabay

Sometimes, even existing and trusted systems have bad days. Take a look at our e-commerce history if you’re wanting for a local example.

During mega-sales periods on e-commerce websites, there have been numerous records of glitches and errors with payments that could take months to rectify. During a Black Friday surge in payments, Maybank’s customers suffered double-charge errors on their debit transactions that drained their money pointlessly. Lazada in 2017 attempted to upgrade their system in preparation of 11.11 sales—a process that caused massive glitches which led to missing orders, missing deliveries, unprocessed refunds, among other issues.

We don’t mean to specifically call out these two institutions, or imply that cashlessness equates to e-commerce; but only to say that mistakes like this can and have happened in Malaysia before. And in a cashless society, we would be left more vulnerable when those situations occur.

The risks with financial institutions though, run deeper than that.

Do We Trust These Institutions With Our Financial Data?

Data breaches: for every system in existence out there, there are approximately a hundred hackers ready to pounce gaps or weaknesses to line their pockets. I don’t know about you, but Malaysian institutions haven’t had the most stellar reputation when it comes to safeguarding our data.

An exposé from Lowyat revealed personal data of regular Malaysians that were up for sale, belonging to Jobstreet.com, the Malaysian Medical Council, the Malaysian Medical Association, Academy of Medicine Malaysia, the Malaysian Housing Loan Applications, the Malaysian Dental Association and the National Specialist Register of Malaysia.

The mother load to Lowyat though, were swaths of customer data from Malaysian telcos—Altel, Celcom, DiGi, Enabling Asia, Friendimobile, Maxis, MerchantTrade, PLDT, RedTone, TuneTalk, Umobile and XOX.

Now all of these hacks could lead to identity theft, which is no small web to untangle if you happen to fall victim. But when it comes to a cashless society, you’d be entrusting arguably, your more sensitive finances to various institutions. And with many of them expanding into unfamiliar financial territories, consumers should keep in mind that these institutions may not have the capabilities to steward that sensitive data in a satisfactory way.

It’s Also Just Unfair

The obvious downside of going cashless is that not everyone will be able to afford the instruments to store their digital money. A 75.9% smartphone penetration is certainly impressive, and while that gap may have closed somewhat this year, that’s still leaving swaths of people in Malaysia without the ability to access cashless payment methods just to live their lives.

This is not to mention individuals with the means of buying a phone, but for various other reasons dislike the notion of going cashless (age, disability, concerned about data security, dislike of specific apps) who could be virtually forced into a system that refuses to cater to them.

This isn’t just a hypothetical either.

Image Credit: Linus Sundahl-Djerf from The New York Times files

Similar signs have become commonplace in Sweden, which is considerered a cashless haven. Apparently the cash declines in 2016 and 2017 were the biggest on record for them. 2017 saw the lowest amount of cash in circulation since 1990, and is more than 40 per cent below its 2007 peak.

We were able to speak to PayNet’s Group CEO Peter Schiesser, to ask; would people be compelled to get off financial services that are deemed outdated, like cash seems to be heading?

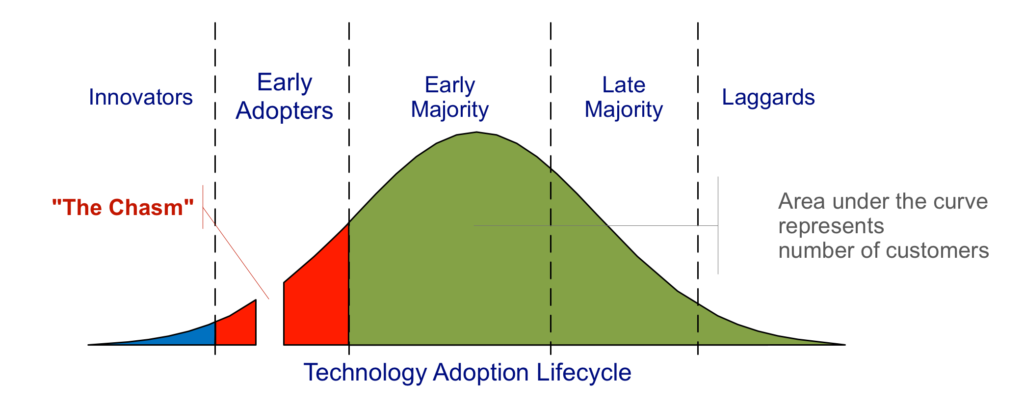

To Peter, it is still a long way before cash is not accepted. And by the time it does arrive he dispels the notion that the situation will be as abrupt as described.

“The problem with the question is that it tends to be an all or nothing question; how do we get to this nirvana state? The reality is that any transition is a curve.”

Peter Schiesser

“So there’s a ramp-up, you get a bulk movement and there’s a long tail. If you come from it to that point of view, you shouldn’t get too hung up on[ whether] we getting everyone there in the right time frame, because that doesn’t happen anywhere.”

When a financial service gets phased out, one would see some great media headlines about someone from the older generation not being able to leave their homes, or other such difficulties of being left behind by technology.

“The thing you’re faced with any deprecating system is that you will have a tail, and you’ve got to be compassionate and understanding [about the fact] that you’ve got to support that.”

But Peter does concede that “there will come a point when you’ve got to make those hard choices.”

Clarifying that this opinion is his own and does not reflect the company’s Peter said that:

“[Those left behind] come in when they’re ready, don’t get over-fixated on that. But from a payments perspective I don’t think it creates a real big disadvantage. I think the financial literacy and access to credit is where they can really be taken advantage of, so to me, it’s more important to do something about that.”

In fairness, it seems like regulators in cashless regions do push back when they see situations like the above occur. In response to ‘no cash accepted’ signs, Sweden’s central bank is forcing major banks to carry certain amounts of cash, and afford “reasonable access” to cashpoints for 99% of Swedes. Meanwhile, the regulator is still trying to figure out the impact of going cashless on consumers, both young and old.

China has also decreed that rejecting cash is illegal following some complaints of merchant’s behaviours.

But then that raises the issue of implementation. After all, it’s supposedly illegal in Malaysia for merchants to impose a minimum purchase for card transactions, and yet you can’t find one Malaysian that hasn’t come across that exact scenario.

I don’t want to imply that Malaysia should wholesale reject going cashless at all. It’s just that these are some very important considerations that we should take into account before we hit a point of no return on our track towards phasing out cash.

While we advocate for cashlessness, perhaps it is not the worst idea to take our time in this case, and ensure that its implementation is not a half-baked measure, and that it accounts for all of the rakyat’s wellbeing.

Luckily for us, there have been various countries that serve as great case studies for us, whether to emulate, or to approach a different way. Now it is all up to us whether we heed them or not.