Comprising over 75 per cent of employment in Southeast Asia, gig workers provide the horsepower to fuel the region’s meteoric rise.

Defined by its speed and convenience, the gig economy consists of individuals providing services on temporary or short-term contracts. These can range from delivery jobs fulfilled by riders to consulting gigs provided by seasoned professionals.

The benefits of the gig economy have been well-trumpeted. For workers, there is the privilege of having flexibility and autonomy in their work. According to the UN Capital Development Fund (UNCDF) report, the greatest benefit derived by workers is the additional income opportunities these jobs provide.

Meanwhile, businesses benefit from ready access to skilled labour – eight in 10 talent managers in the Asia-Pacific region report hiring or using gig workers.

While the value provided by the gig economy is clear, let us focus on the elephant in the room instead – that gig workers are not financially included. For the average gig worker, their earnings are often their main income source. However, the unpredictable nature of these earnings makes it difficult for gig workers to furnish a consistent income history.

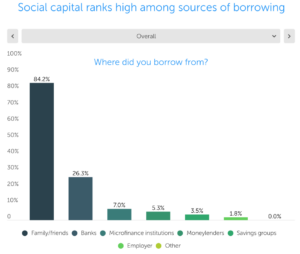

This handicaps them in gaining access to basic financial services such as loans. Therefore, over 80 percent of gig workers borrow from their family and friends instead.

Friends and family are the preferred borrowing sources for gig workers. (Image Credit: UNCDF)

Root cause

However, the lack of income history is not the primary cause of this problem. Instead, it is the limited finances and financial literacy among gig workers.

As these workers enter the gig economy primarily to meet their daily expenses needs, they can rarely afford to save. In the same report, only 13 per cent of ride-hailing and food delivery riders in Malaysia indicated they have the desired financial freedom. Meanwhile, only 18 per cent are comfortable dealing with a financial emergency of MYR 1,000 (US$250).

Acknowledging this issue, Malaysia’s GoGet, an on-demand work platform that connects businesses and consumers with verified gig workers for flexible tasks like deliveries, introduced “Pod” – a micro-savings platform developed by local fintech firm SaphX Technologies.

Pod aims to cultivate a saving habit among its users by allowing them to directly debit a fixed amount into their bank accounts weekly.

However, its uptake among GoGet workers has been less than ideal. Only 1 in 6 reported using the platform. Those with higher educational attainment, earning more than MYR 60,000 (US$14,200) annually, and relying on GoGet as the sole income source formed the majority of Pod users.

Meanwhile, 44 percent of those who do not use it stated they did not understand how the platform operated, while another 40 percent cited insufficient money.

Raising wages

These figures point to two distinct challenges of providing digital financial products for gig workers – the exclusion of technology laggards and limited finances. While the former can be solved by improving usability, the latter is harder to tackle.

For gig workers to improve their financial wellbeing, they will need to increase their earnings. This can be realised by increasing the number of gigs worked or the commission earned per gig. The latter is a more sustainable approach. However, it remains to be seen if gig economy platforms are willing to sacrifice their commissions and profits for that to occur.

Meanwhile, Grab has rolled out a slew of initiatives targeted at increasing the financial inclusivity of its workforce.

Its GrabAcademy platform offers financial literacy courses by Standard Chartered. GrabInsure, the super-app’s insurance arm, offers usage-based motor insurance for drivers and delivery riders.

This allows them to pay for daily insurance only when they are working for Grab, with premiums starting from MYR 1 (US$0.25) per day. Grab claims this pay-per-use insurance is more affordable and accessible to gig workers.

The company also partnered with NTUC Income, an insurance co-operative in Singapore to launch a similar micro-insurance plan covering critical illness for its Singapore workforce. Its drivers and delivery riders pay premiums starting from US$0.10 per trip for a fixed amount of insurance.

To tackle the difficulty in accessing credit for gig workers, Grab took things into its own hands and launched a credit facility in Indonesia.

Workers can register for loans of up to IDR 5 million (US$350) with “affordable” interest rates. Loan repayments can be made daily via direct deduction from the worker’s digital wallet. The facility is available to 1000 Grab drivers as part of a trial phase.

Will there be financial inclusion?

For many lower-to-middle class gig workers, earnings from platforms such as GoGet and Grab often represent their sole source of income. Barely able to meet their daily expenses, these workers can rarely afford to save or purchase more sophisticated financial products such as insurance or investments.

While gig economy platforms have started to tackle these issues through initiatives aimed at increasing financial literacy and access, these are band-aid solutions at best.

To tackle the root cause of the issue, gig platforms need to pay their workers better. However, such a move seems implausible, given many of these platforms are still in the red. Until then, financial inclusion for gig workers will remain a far-fetch goal.